Advanced Marathon Training Techniques

By Roy Stevenson

At some stage of their running career, all marathoners stop improving, even seasoned ones with several marathons under their belt. If you've reached a plateau where your times are getting slower, it might be time to reevaluate your marathon training program.

Likewise, if you've been getting sick or injured frequently over the past year or two and suspect you're overtraining, restructuring your training program might be long overdue.

Even experienced marathoners need to reexamine their training periodically. So if you've been running consistently for 3-5 years, and can run 50-70 miles per week, here's some advice to help you reassess your training schedules, with the goal of cutting time off your next marathon.

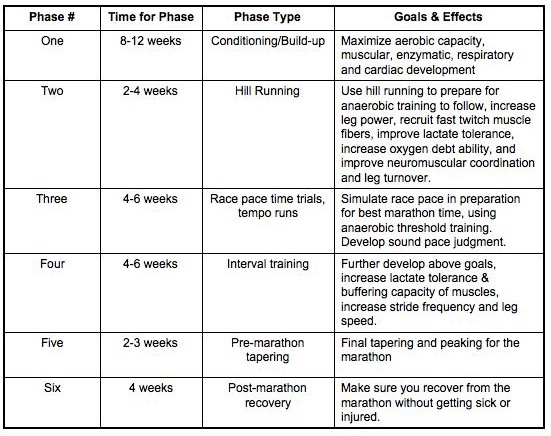

Your Marathon Training Phases

Your program needs some structure, and this program provides definite start and end points for each phase. Collectively, the segments resemble Arthur Lydiard's marathon training system, but I've made a number of significant changes in light of what exercise science research has shown us in the past two decades.

Phase One: Marathon Training Conditioning

A Weekly Schedule for the Conditioning Phase. Insert short 20-30 minute, slow morning jogs where suitable.

Monday - 45 minute slow run

Tuesday - Fast Workout

Wednesday - 1.75 hour slow run

Thursday - 45 minute slow jog

Friday - Rest day

Saturday - 2.0-3.0 hour slow run. This can be reduced by 30 minutes every other week

Sunday - 1.5 hour slow run

Frequency of Your Marathon Training Runs

Start by looking at your number of training sessions each week. You need a minimum of 4-5 days. Six is OK too, but leave seven to the Kenyans. Even the creator rested on the seventh day.

During your conditioning phase you can run twice daily by adding a shorter jog in the mornings, at a very slow pace, if you feel you can handle it. You need only add one or two of these twice daily efforts to each week. They can be 20-30 minutes long, and purely for additional aerobic conditioning.

Your Long Endurance Runs

Three long runs each week should form the cornerstone of your marathon training program. These develop your endurance capacity by improving your body's ability to consume oxygen, or what exercise physiologists call maximal oxygen uptake (also referred to as VO2 max).

These long endurance runs are what will get you across the marathon finish line. In fact, most beginning marathoners are better off concentrating solely on longer runs to develop their endurance enough to finish the 26.2 mile distance, even if they do no running between them.

You'll notice I'm recommending long runs of up to 3 hours-about 22 miles if you run at 8 minutes per mile pace, or 20 miles at 9 minutes per mile. These are necessary because the muscles adapt to the wear and tear of these long efforts by repairing themselves and becoming stronger.

The formidable list of damage done during long runs of 2-3 hour duration includes ruptures and tears in the muscle fibers, depleted glycogen stores, severe inflammation, spillage of intracellular contents outside the muscle, swelling, displaced red and white blood cells, degenerated mitochondria, and high levels of stress hormones, to name a few.

But inflicting muscle damage is merely part of the marathon training process, and should not present a problem to the healthy runner, providing they get enough rest, watch stress levels, and eat a healthy, balanced diet to facilitate anabolic muscle regeneration.

However, a myriad of other more positive changes take place too-an increase in the size and number of mitochondria in the muscle cells (the little powerhouses within each muscle cell), an increase in the size and number of blood capillaries, improved aerobic enzyme function for metabolizing carbohydrate and fats, improved efficiency of your respiratory muscles, and enhanced cardiac output, and many more.

The long runs should be spread out, at least 2 days apart, for recovery. Your muscle tissues need to repair, glycogen stores need to replenish, and you need to mentally recover from these long efforts. How long should they be? 1.5 hours to 3.0 hours.

Despite my advice to spread out the long runs over the week, you'll notice that the weekends are stacked up with a long run on Saturday, followed by a (not quite as) long run on Sunday. This is a trick Lydiard's New Zealand athletes used to maximize their aerobic conditioning. You'll feel flat on your Monday run, but by Tuesday you'll be running so much stronger, wondering where it all came from.

The Speed of Your Long Endurance Runs

When you are in your conditioning cycle, your long running can be as slow as you like-in fact, when starting out you should deliberately keep your pace slow. Run at a comfortable pace where you can talk. You'll find these long runs will get progressively faster as you get fitter, without any apparent extra effort. Change the course and terrain for each long run, and note the times for each run in a training diary.

To better handle this increased mileage and avoid overuse injuries, sore legs and those niggling pains that often afflict runners at this stage, run slow, run easy, and use a heart rate monitor to ensure you are staying within your "easy" training zone. And avoid racing during this time.

Avoiding Injuries and Leg Soreness

If possible, run on soft surfaces such as cross country, golf courses, farmland, forests, dirt trails, or sawdust trails at least a couple of days each week. Lydiard's athletes have used this old trick for decades in New Zealand to keep their legs from getting too sore from the pounding on the road surface.

The Length of Your Conditioning Build Up Phase

Since aerobic adaptations are relatively slow, this phase should be from 8 to 12 weeks. Advanced marathoners, who train year round and are already in good condition, may only need 8 to 10 weeks of this conditioning.

Using Perodization Principles to Help Adapt to Mileage

Here's a twist to the standard conditioning format that will help you handle it better. Instead of grinding out the same mileage every week, back off your mileage every third week. Cut back during your easy week by simply lopping 25 minutes off each training run.

By programming in this lower mileage recovery week every three weeks you'll recover from those long runs better and reduce your chances of overtraining and getting sick.

This approach, where your running volume increases for two weeks followed by a shorter, easier week, is called periodization, and it enables your body to adapt more efficiently.

You'll bounce back the following week with renewed energy and mentally refreshed from the reduced mileage. I'm always amazed at how many marathoners just do the same weekly mileage over the same courses, at the same pace, week in and week out every year, often burning out. Using periodized schedules will revolutionize a stale runners' program.

Consider Adding in a Fast Day During Your Conditioning Phase

Advanced marathoners should add a day of faster running into their marathon training conditioning schedules. This is considered heresy in traditional Lydiard circles, but these faster running days keep your leg speed from slowing down by stimulating your neuromuscular system at a higher level.

Additionally, you'll work your anaerobic threshold up a notch or two, and get a good "blow out" to make sure you're not just becoming a long, slow distance runner. These faster workouts can be a fartlek run on cross-country, trails, forest, or road, or slower interval training repeats on the track.

The track intervals don't need to be elaborate, finely tuned, strenuous anaerobic workouts that you can barely walk away from. The idea is just to get you running at a faster pace to get you out of that long, slow distance plodding.

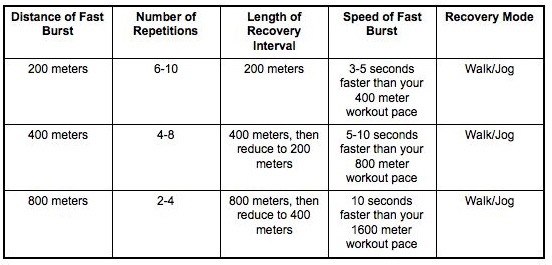

Some suggested workouts and guidelines follow. As you can see from these interval workouts, there's nothing magical about them. The sole purpose is to get you revving over at a faster pace--not to bust your chops like you did in your high school track days. Make sure you have a good warm up of at least 20 minutes jogging, some stretching, and some stride outs over 50 meters.

A Sample Fartlek Workout

One of my favorite fartlek workouts is 15 minutes jog (warm-up), a hard 5-minute burst, a recovery jog of 3-4 minutes, another hard 5-minute burst, a recovery jog of 3-4 minutes, then five or six fast pace stride outs over 200 meters, followed by a cool-down jog.

Now you've completed your 8 or 10 weeks of conditioning, it's time to start adding intensity to your program with hill running.

Phase Two: Hill Running

An essential component of a marathoner's training program, hill training reaps many dividends --but I have modified Lydiard's hill springing and bounding technique because of its high potential for injury to the Achilles tendon, ankle, calf, quadriceps, hamstrings, and hips.

I've watered it down by changing the mechanics of this action to simply striding at a faster pace uphill (I didn't say it would be easy).

Sample Schedule that Includes Two Hill Running Workouts Each Week:

Monday - 45 minute slow run

Tuesday - Run hills on your course hard for one hour

Wednesday - 1.5 hour slow run

Thursday - Uphill repeats session in 45 minute workout

Friday - Rest day

Saturday - 2.0 hour slow run

Sunday - 1.5 hour slow run

What are the benefits of hill running? You'd be surprised at how much research has been done on uphill running--here's a summary of what research has found.

Uphill running increases stride length-- the hip flexors become stronger, and pull our legs through higher, leading to a longer stride. Stronger ankles lead to increased stride frequency, thus a faster leg turnover. If you run faster downhill, your neuromuscular system will also adapt to a faster leg turnover.

Anyone who runs up hills will tell you they breathe much harder--your VO2 max increase significantly while hill running versus running on the flat. Coupled with this, your running economy improves, so you'll use less energy over longer distances.

Hill training increases your lactate threshold, so your body adapts by metabolizing lactic acid and resynthesizing it as fuel. Thus you won't get as fatigued when running at any given pace. This is great preparation for the time trials and tempo-running phase you'll be doing next.

If you train hard on hills, you'll run the uphill sections of your races faster. So if you're running a hilly marathon, you'll be better prepared than most of your competitors, and they'll be left struggling behind.

Hill Running Technique

Concentrate on driving your arms harder and lifting your knees a little higher, while still striving to holding your form. Your aim is to become smoother while running faster on the upgrade.

Two Workouts for Hill Training:

The first way to utilize hills is to simply accelerate gradually up each one on your training route, maintaining a sub maximal pace that's just below your maximal threshold. i.e. if you speed up any more, you'll end up walking.

You'll find in your early uphill efforts you'll have to slow down towards the top. However, if you persist, you'll go a little further on each outing at your faster pace, your breathing will get easier and your legs will not feel so fatigued and heavy.

The second variation is to select a steady uphill slope, not too steep, and do a number of repeats up it. After warming up, start with 4 fast running bursts up the slope, over a distance of 100 to 200 meters, then walk or jog slowly back down to the start. Increase the repetitions by 2 on each subsequent session, to 6, then 8 then finally 10 repeats.

Phase Three: Marathon Training Race Pace Time Trials and Tempo Runs

Most exercise scientists who study the effects of endurance training, and coaches of marathoners agree that the most important predictor of success in this event is the ability to cruise at a high percentage of one's VO2 max.

Legendary New Zealand coach Arthur Lydiard, in his book Running The Lydiard Way says, "The idea is to run trials under the distance you are training for. Time trials are most important in bringing about coordination of speed and stamina".

A time trial (often referred to as tempo running) is simply running "at a pace that produces an elevated yet steady state accumulation of lactic acid", according to Jack Daniels, PhD., in his book Daniel's Running Formula.

Because of the grueling physical and mental toll, these high intensity efforts should only be done once each week. An easy concept to understand, time trials are much less fun to implement.

You've already developed your body's ability to consume large amounts of oxygen during the conditioning phase, so now it's time to improve your ability to run closer to your maximal aerobic capacity for longer. This is where race pace tempo runs and time trials enter your arsenal of training techniques.

You do this by dipping slightly into your anaerobic zone, where you start accumulating lactic acid faster than it can be metabolized or broken down. This is called Lactate Threshold, sometimes referred to as onset of blood lactate accumulation (OBLA), or even anaerobic threshold.

There is some debate between the new breed of exercise scientist and the old guard over whether lactate accumulates due to insufficient oxygen in the muscle tissue, or from the increased breakdown of carbohydrates during lactate threshold, and that perhaps it's the increased concentration of hydrogen ions, a by product of lactic acid in fatigued muscle that causes the feeling of tiredness--but regardless of the physiology, for practical training purposes, time trials or tempo runs still have the desired training effect.

Most good runners can work at only 75% to 80% of their aerobic capacity during a marathon. Amazingly, some of the world's best marathoners have had their anaerobic threshold tested, and were found to race marathons at 90% of their maximal aerobic capacity. Astounding!

You'll be doing your lactate threshold time trials somewhere between 70% and 85% of your maximal aerobic capacity, which corresponds with about 78% to 91% of your maximal heart rate.

Establish your maximal heart rate by subtracting your age from 220--a rough guide at best because considerable variation exists between our maximal heart rates. The easiest way to establish your maximal heart rate is to go and run one mile on the track as hard as you can while wearing a heart rate monitor, and note your peak heart rate.

Once you've established your maximal heart rate, calculate your lactate threshold pace back by calculating 82% to 91% of maximal heart rate. When starting time trials, it's wise to start at the low end of the recommended heart range. i.e. 82% of your maximal heart rate.

Your goal is to maintain a strong steady pace all the way, hence the importance of checking your pace every mile for consistency. Your heart rate monitor will help you zero in on a steady, constant heart rate to cruise at.

How do you know when you're running at lactate threshold? Oh, you'll know all right-shortness of breath, heavy legs, a burning sensation in your muscles, and poor coordination. You can use these subjective symptoms to gauge whether you are running at lactate threshold or close to it.

If you find your pace too easy, speed up a little until you find your threshold using the symptoms above. Your heart rate during time trials should be about 15 beats per minute faster than during your standard long training runs.

Tempo running is grueling, but if you don't practice running at your lactate threshold point, you'll run much slower than you should in your marathon and races over lesser distances and cheat yourself of achieving your true marathon potential.

A Marathon Training Schedule that Includes One Tempo Running Workout Each Week:

Monday - Easy 45 minute run

Tuesday - Time Trial run over 5K, 8K, 10K, 10 miles or half marathon

Wednesday - 1.5 hour slow run

Thursday - Easy 45 minute run

Friday - Rest day

Saturday - 2.0 hour slow run

Sunday - 1.5 hour slow run

How to do Time Trials and Tempo Runs

Choose a flat measured distance (see below for recommend distances) on a road or track. Warm-up for 10-15 minutes jogging followed by a few stride-outs over 50 meters. Push yourself over your selected time trial distance at a sub maximal threshold pace. The pace should be faster than your marathon pace, but slower than your 10K pace, ideally somewhere around your half marathon racing pace.

You're aiming to finish your time trials at the same pace you started. You should be left with some reserves when you finish time trials, not be exhausted. In fact you should do a 10-15 minute cool down jog to ease your muscles and resynthesize the waste products that have built up. Time trials also give you the opportunity to practice ingesting sports drinks and/or energy gels to find out what works the best for you.

Note your finishing times for these efforts, and try to better them slightly in subsequent time trials. Ideal distances for time trials for marathoners are 8K, 10 miles and half marathon. Given that the time trial phase is 4-6 weeks, you might start with two or three 8K-time trials, and then move up to one or two 10-mile trials, and finally one half-marathon effort.

To get a reasonable prediction of what your actual marathon time will be, double your half marathon time. You should come in a bit faster than this in your marathon in a few months time because you still have to do the interval training phase, and the added stimulus of competition in the marathon will have you running faster.

Time trials train your body to use less muscle glycogen during the marathon, thus prolonging your energy stores. You'll accumulate less lactic acid at any given pace, enabling you to cruise at a faster pace, increasing your endurance capacity.

This all translates into your developing the ability to push yourself over the entire race distance, so when you toe the start line, your body (and just as importantly your mind), are used to thrashing yourself over that distance.

You'll also find that towards the end of the marathon, when people are flagging and starting to slow down, you're maintaining your pace and form, and perhaps if you're having a really good run, speeding up slightly. Either way, you're pulling ahead, and your time will reflect this.

Time trials also help you perfect pace judgment. This valuable skill helps you run your marathons at even pace, so that your second half is the same or hopefully faster than, your first half. This skill gives you a tremendous advantage over the rest of the marathoners--running even splits or negative splits is by far the most efficient way to get your best marathon time.

So while you're struggling through your time trials, think of the manifold benefits you're gaining to keep you going.

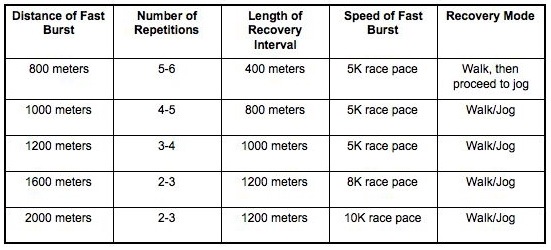

Phase Four: Interval Training

Interval training can be looked at as the icing on the cake. This final sharpening phase will have you jumping out of your skin by race day.

Sample Weekly Training Schedule that Includes Interval Training Workouts:

Monday - 1 hour slow run

Tuesday - Interval Training session

Wednesday - 1.5 hour run

Thursday - 1 hour steady pace run

Friday - Rest day

Saturday - 2nd Interval Training Session (if under 35 years old), otherwise 1-1.5 hour run for age 35 and over

Sunday - 2.0-3.0 hour slow run

For runners over 35, one interval workout each week is all you need. As we age, our muscle cells, connective tissues, tendons, ligaments, etc, lose their elasticity and tensile strength, and it takes longer to recover from intervals.

Benefits of Interval Training

The many benefits of intervals to the marathoner make this fast paced running well worth while: enhanced utilization of fats and carbohydrates, longer stride length, improved running economy which translates into decreased oxygen extraction at sub maximal pace, increased maximal oxygen consumption at maximal pace, and improved lactate tolerance, which delays fatigue.

Track interval workouts are well defined. You run a certain number of repetitions over a set distance, at a predetermined speed, with walking or recovery jogging between the fast bursts. The amount of recovery between the fast bursts should be about the same as, or slightly less than the time spent in the actual fast burst. The recovery can be done at a walk, and as you improve your fitness, a slow jog.

According to Pete Fitzinger, in his book, Advanced Marathoning, the interval bursts need to be between 3 and 10 minutes. Jack Daniels, in his book Daniel's Running Formula, prefers interval bursts between 3 and 5 minutes. The workouts below cover both bases.

Progressing Your Interval Training

Progress your interval workouts as you adapt to them by taking a shorter distance to recover, or speed up the fast bursts, or increase the number of repetitions, or go from walking to jogging during the recovery. But only ever change one of these at a time, as interval training can plunge you over the abyss into the dark void of overtraining in a few short sessions.

Start with the lowest number of repetitions and proceed to add 1-2 reps/week until you hit the maximum number recommended on this table. Rotate these workouts each week. For example, on Week 1, do 4 x 800 meters, then Week 2, do 4 x 1000 meters, Week 3 do 3 x 1200 meters, etc., until you have come full circle.

You'll do these interval bursts at 80% to 90% of maximal heart rate--somewhat faster than your time trials.

Putting It All Together: Designing Your New Marathon Training Program

Your revised marathon training program now consists of a series of phases that lead from one to the other. Very few marathoners can get through any sequence of training phases without interruptions of some sort; illness, muscle soreness, travel, work and family demands, inclement weather, etc.

You'll need to be flexible here. Our body does not adapt in the linear fashion that these schedules are laid out, so sticking doggedly to training schedules can cause problems. If you're feeling under the weather, sore, exhausted, mentally tired, don't be afraid to take a day or two off--put your feet up in front of the fire, and read the newspaper with a cold beer at your side. A day or two of rest, if applied judiciously, is probably what your body is demanding.

If you feel exhausted and unready to tackle any of the high intensity workouts outlined here, try slow easy recovery jogs of 30 minutes until you feel better. Once your legs and breathing are fine, and your energy has returned, it's time for your next high intensity workout. If not, jog again that day and see how you feel the next.

You'll notice two long runs are included in every phase of this marathon training program. They should eventually become pro forma, and be something to look forward to. If you need to reduce a long run temporarily because of fatigue, do so without guilt.

Phases five and six, tapering for the marathon and recovery are beyond the purview of this article. There is no shortage of good advice on these crucial aspects of marathon preparation on the Internet and the many excellent running books on the shelves of your local bookstore.

If you stick with these phases, following them as closely as possible given your circumstances, you should run your best marathon, or return to your recent best performance level. Stay with it-and have the faith that as you line up for your next marathon, you are one of the best-prepared runners.

You can find additional information at my running website: www.running-training-tips.com.

References:

Advanced Marathoning, 2nd Edition. Pete Fitzinger & Scott Douglas. Human Kinetics. 2009

Daniel's Running Formula, 2nd Edition. Jack Daniels, Ph.D. Human Kinetics. 2005

Exercise Physiology: Energy, Nutrition, & Human Performance. 6th Edition. William McArdle, Frank Katch, Victor Katch. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2007

Inside Running: Basics of Sports Physiology. David Costill, Ph.D. Benchmark Press. 1986

Run to The Top, Arthur Lydiard & Garth Gilmour. A.H. reed, 1962.

Serious Training for Serious Athletes. Rob Sleamaker. Leisure Press. 1989.

Running Your Best, Ron Daws. Stephen Greene Press. 1985

Sports Physiology, 3rd Edition. Richard Bowers & Edward Fox. Wm Brown. 1992

Return from Marathon Training to Running

Return from Marathon Training to Home Page