The Mysterious Green Man

in Medieval History

By Roy Stevenson

You see the green man lurking everywhere in historical buildings around Britain and old Europe. His face can be found, half hidden by surrounding leaves, and long vines sprouting from his nostrils and mouth on the cornices of ancient European buildings and atop Roman columns in Gothic cathedrals.

This secretive sprite appears in medieval manuscripts, bookplates, tapestries, and bright stained glass windows, his fierce visage glaring at you with pagan malevolence. Untold British public houses are named after him, as recorded by an unknown writer. “They are called woud men, or wildmen, thou at these day we in ye sign (trade) call them green men, couered with grene boues: and are used fir signes by stiflers of strong waters".

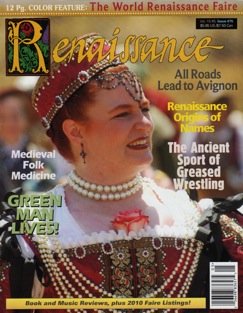

Sometimes you’ll see him in the flesh, painted forest green, covered in a tangle of brown or green foliage, leaves, or brightly colored flowers. He’ll be capering around, leading a parade in London or in some small cobblestone village square in France, Germany, or Switzerland.

Every January he parades through the streets of Basle, Switzerland, bedecked in green, holding an uprooted tree. He appears at the Garland Ceremony in Castleton, Derbyshire, in May, on horseback, wearing a cone-shaped frame covered in leaves and thick bundles of beautiful flowers, leading the street parade.

The green man did sterling duty as a ‘whifler’ in 16th and 17th century Lord Mayors Pageants and parades, clearing the way through crowds with flaming torches and fireworks. Matthew Taubman, in 1686, described his antics thus, " in front of all before these, twenty savages or Green men with Squibs and fire-works, to sweep the streets and keep off the crowd".

Evidence of the green man is found in abundance in France. He’s on the 4th century AD tomb of Saint Abre, the daughter of St. Hilaire, a pagan who converted to Christianity to become one of its leading lights. You can see him on a fountain at the Abbey of Saint-Denis near Paris, dated around 1200 AD, with the inscription ‘Silvan’ carved on it, a reference to the Roman forest god by the same name.

And of course, every Renaissance Faire worth its salt has a green man. But if you ask him who he is, you’ll be lucky to get a clear answer. The origin of this mysterious creature is obscurely shrouded in the bygone past and the folklore surrounding this ‘Jack-in’the-Green’ is endless. The abundance of foliage growing out of his mouth, nose, and ears cause many to associate him with growth and nature, perhaps a symbol of the cycle of growth being reborn each spring.

Other superstitions see him as a malevolent forest spirit, not quite human, capable of doing good, impish mischief, or even foul harm, depending on his mood. He was greatly feared for his capricious unpredictability. The forests in the middle ages were unsafe places, full of robbers and rapists, to the extent where dirt roads through them had to be cleared to allow for a bowshot on either side of the road. Demons could even take the form of walking trees. Many a mother would have told her children to be home from the forest before dark “lest the green man get you”.

He’s been otherwise interpreted as an early symbol of lust and primal unredeemed man, a kind of Bacchus, representing undisciplined erotic passion. And he's probably a remnant from pagan times—perhaps a fertility figure or a spirit of nature, a wild man of the woods who survived the Christian purging of pagan symbols in the first few hundred years after Christ.

In an attempt to placate new converts, many churches chose to adopt pagan gods and deities, even turning some into ‘unofficial’ saints—hence the green man’s frequent appearance in early Christian churches and cathedrals. Rosslyn Chapel, not far from Edinburgh, boasts no less than 103 representations of the green man inside the chapel, and dozens more outside on the roof and walls.

By and large, the green man disappeared in the early middle ages, to undergo a renaissance of sorts during the Gothic architectural period (12th -15th centuries), where his face reappeared, often in stylized versions, in churches, chapels, abbeys and cathedrals. His countenance appears in many British Cathedrals including Bristol, Wells, Gloucester, Winchester, Canterbury and Chichester, and in London’s St Paul’s Cathedral and Westminster Abbey. Historians believe that his re-emergence was purely for decorative effect, rather than from a renewed belief in this entity.

The Gothic green man’s visage takes on many personas—he’s often seen scowling in pain, or looking somewhat resentful, and sometimes looks like Old Nick himself, complete with horns. From the 15th to 17th centuries he became more serene and peaceful, when he appeared on public buildings and houses.

His most common forms are the foliate head, where his face is completely covered in leaves; the disgorging head, where vegetation spews from his mouth; or the bloodsucker head where he sprouts vegetation from his facial orifices. Once you know what to look for, his various guises and incarnations is seemingly everywhere. But he’s often overlooked because he’s not one of the apostles or a long-dead pope or cardinal, so you glance at him uncomprehendingly, then cast your gaze away at the other statues, carvings and paintings that adorn Europe’s cathedrals and public buildings.

No matter what the green man’s origins, his legacy remains carved into bench-ends, roof bosses, misericords (hinged wooden seats), church walls and ceilings, cornices of houses, churches, abbeys, cathedrals, and town halls, all over Europe. You’ll be amazed at how his leaf-encrusted face suddenly pops out at you, as if by magic, when you’re visiting these places, leaving you wondering who he really is.

Return from Green Man to Travel & Culture

Return from Green Man to Home Page