The Battle of Waterloo

and the Crucial Role of Artillery

By Roy Stevenson

The Battle of Waterloo was one of the pivotal military events of the first half of the 19th century. Small wonder that it is the most publicized battle in history. This series of battles that culminated in great bloodshed on the gently sloping farmlands of Waterloo, only 12 miles from the center of Brussels, prevented Napoleon from regaining ultimate control over Europe. Had its outcome gone differently, Europe’s balance of power would have been significantly affected, at least for some years or even decades until self-appointed emperor Napoleon would have finally been put in his place by renewed coalitions of his enemies.

That the Battle of Waterloo could have gone either way but for a series of errors of judgement on Napoleon’s part, is generally acknowledged by military historians of the era. Wellington himself realised how close it had been when he remarked soon after the battle, “it was . . . the nearest run thing you ever saw in your life”, a catch phrase now recorded in history.

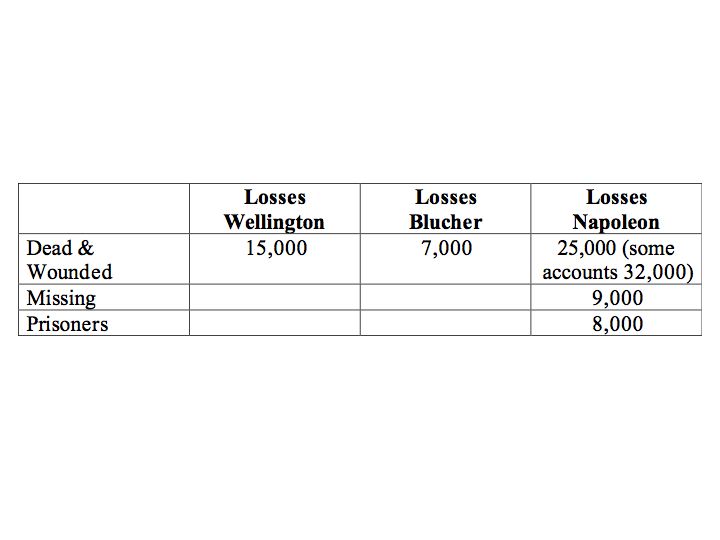

It is generally (and often grudgingly) acknowledged that it was the arrival of Blucher’s Prussian forces several hours into the battle that finally tipped the scales in Wellington’s favor, just when his troops were reeling and being worn down from Napoleon’s constant assaults. But Napoleon’s misuse of his artillery (and Wellington’s canny utilisation of the same) also contributed greatly to the outcome, perhaps more than most historians realize.

Artillery was used extensively at Waterloo, and the preceding battles at Ligny and Quatre Bras, by both Wellington and Napoleon, and proved amongst the crucial deciding factors for the final outcome. Here’s how artillery was used in these battles, and for those of you fortunate enough to be able to visit the battlefield some day, a listing of museums, monuments and buildings that can still be seen there, follows.

Prelude to the Battle of Waterloo (April-June, 1815)

Napoleon escapes from his imprisonment on the Island of Elba and marches on Europe to reclaim his self-proclaimed empire. He rapidly advances on Wellington’s forces encamped at Brussels, (in what is now Belgium). Wellington leads an army of allies from several nations including Britain, the Netherlands, the King’s German legion, Hanoverian regulars, the Duchy of Brunswick, and of the Duchy of Nassau, to put a stop to Napoleon’s ambitions once and for all.

The Battle of Waterloo is actually the climactic battle in a series of encounters starting in Charleroi (June 15, 1815), proceeding through Ligny and Quatre Bras on June 16, and culminating in the Battle of Waterloo two days later. Blucher’s Prussian army and Wellington’s Allied Army have not yet united, so Napoleon wants to attack them while they are still divided—otherwise he is seriously outnumbered.

Thus, June 16, 1815 sees the rather unusual military phenomenon of two battles raging simultaneously only 6 miles apart. One in the small country village of Ligny and the other at a major road intersection further west, called Quatre Bras (literally translated meaning “four arms”).

The Battle at Ligny

Fighting at Ligny takes place between 2 p.m. and 9 p.m. between one Corp of Napoleon’s army and the 73-year-old Prussian General Gebhart Leberecht von Blucher’s army. By day’s end Blucher has been defeated after fierce fighting and retreats 18 miles north to Wavre, with the French in rather lackadaisical pursuit. Blucher’s nose has been bloodied, but he’s as tough a military commander as history has seen, stoked by a passionate hatred of the upstart Napoleon and everything he stands for. His plan is to march to Wellington’s aid, once Wellington has decided where to make his stand.

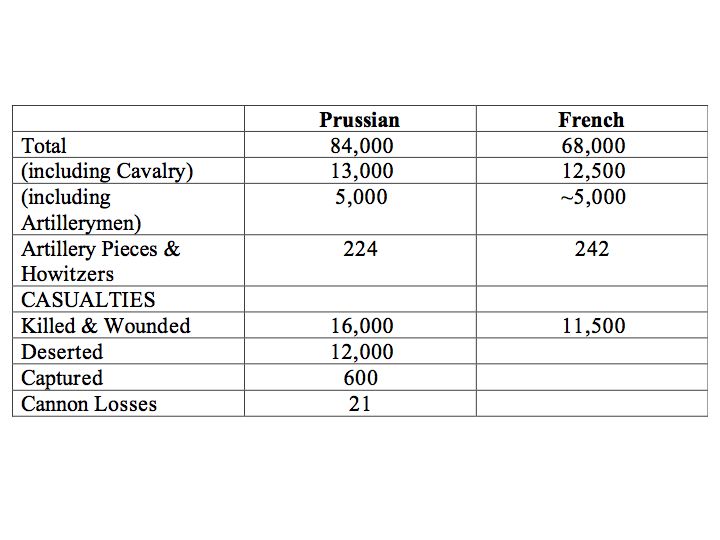

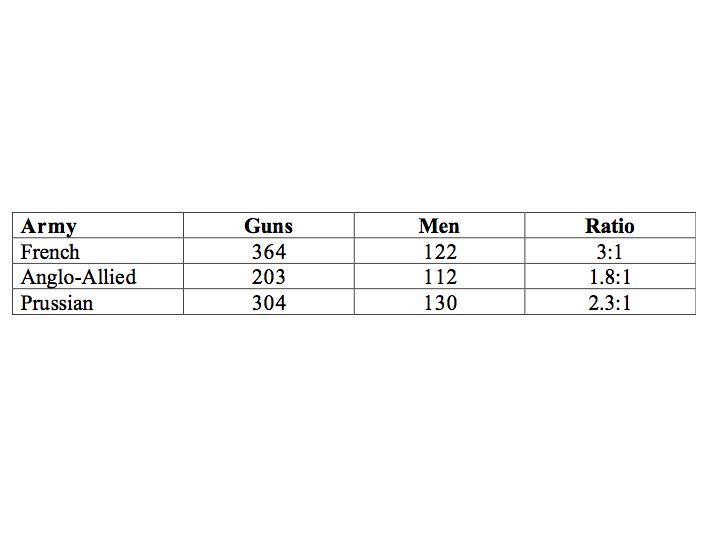

Battle of Ligny-The Beligerents

Battle of Ligny - The Beligerents

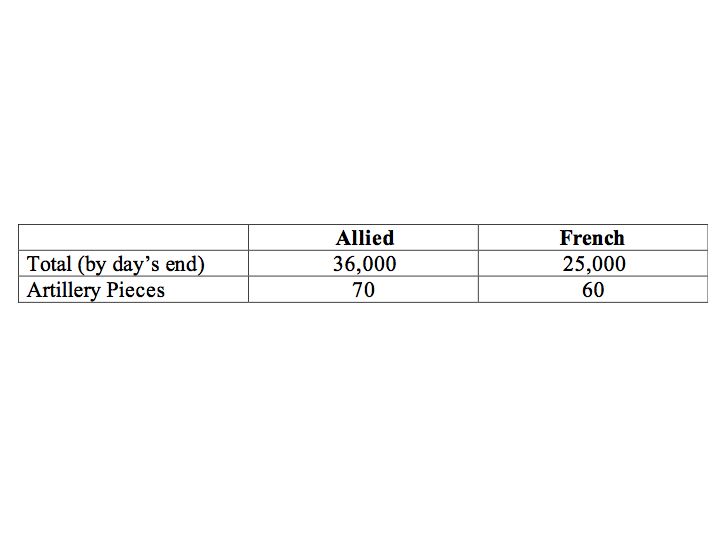

Battle of Ligny - The BeligerentsThe Battle at Quatre Bras

The Battle at the Quatre Bras Crossroads starts with relatively small numbers of troops on both sides, but reinforcing troops on both sides stream in all day escalating the fighting. This battle takes place between 2:30 p.m. and 7 p.m.

The French generals Ney and Reille have the numbers advantage earlier in the day but the appearance of Dutch-Belgian Divisions, Brunswickers and British turn the tide against the French. By 7 p.m., Ney’s men are in retreat. This would have been a good opportunity for Wellington’s forces to force the French to capitulate, but because Blucher’s men are retreating to the north towards Wavre, he cannot press his advantage for fear of being outflanked by Napoleon.

Wellington and Blucher Retreat

Instead, now, Wellington must withdraw his forces north the next day (June 17), ten miles to Mont St. Jean, (2 miles from Waterloo) to avoid being outflanked by the French, because Blucher’s forces are retreating. Wellington, always planning ahead, had visited Mont St. Jean the previous year and scouted it as a good defensive position for a major battle so he withdraws his troops to this spot.

Blucher is wounded at Ligny, but still has plenty of courage. He wants to continue fighting the French, whom he hates intensely. While agreeing to support Wellington at Mont St. Jean both Blucher and Wellington know it will take his dispersed forces many hours to march southwest the 8 miles from Wavre to Mont St. Jean. All Wellington can do is hope Napoleon will not attack early on the morning of June 18, thus allowing the Prussians enough time to arrive on the battlefield. Another of Wellington’s most famous quotes on the day of the battle is, “give me darkness or give me Blucher”.

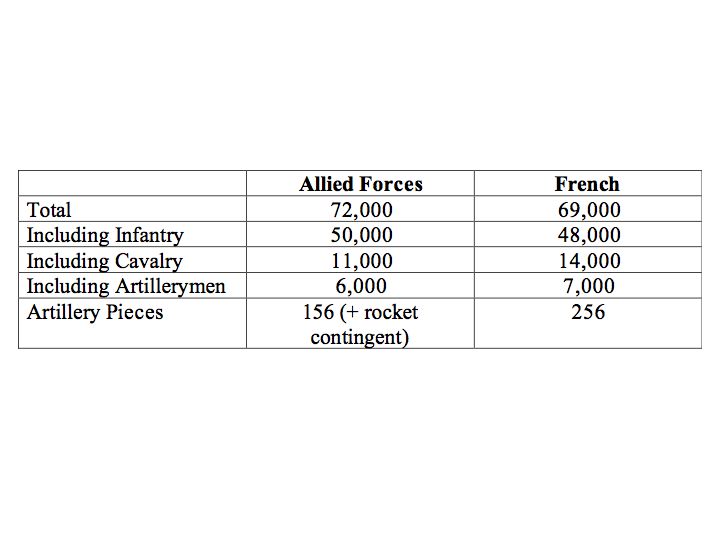

The Armies at Waterloo

The French and British Artillery

The French artillery, the Grande Batterie, is the most proficient in Europe, with new gun designs by Jean-Baptiste Gribeauval. Napoleon’s Imperial Guard infantry brigades each have a 6-pounder foot battery and each cavalry brigade has a mobile 6-pounder horse battery. There are four 12-pounder batteries (called his “beautiful daughters” by Napoleon) attached to the Imperial Garde Headquarters.

The British are technically the equal of the French artillery with mostly 9-pounders and 5.5 inch howitzers, plus some mobile 6-pounders for the horse artillery and Congreve rockets. A dozen 18-pounder siege cannon did not see any action as they were left behind due to the rapid deployment of Wellington’s forces. One wonders however, what might have happened if these 18-pounders were present on the battlefield to unleash their carnage on the French. It would be presumptive to say that they would have made all the difference, nevertheless they would certainly have been of concern to Napoleon, and could have forced him to proceed more cautiously.

Guns per thousand men for the Campaign:

The French and British Batteries

Each battery on both sides consists of four to six guns and two howitzers. The guns are fired on a flat trajectory, while the howitzers’ short barrels permit high-angle fire. The battery proper comprises 90-150 artillerymen, with a separate squadron of 75-150 men who transport spare ammunition, and do repairs.

Artillery Tactics During The Battle of Waterloo

Napoleon started his military career as an artillery lieutenant in the French army and his battles reflect this experience. He prefers to use his artillery offensively, battering the enemy’s infantry with shot and shell until they are sufficiently softened up to send in his infantry or cavalry. He deviates from this tactic at Waterloo, by not permitting his artillery to complete their grim work before committing his cavalry and infantry. This fatal mistake is repeated time and again during the battle.

Wellington too, has a sound grasp of effective artillery tactics, with the advantage of being on the defensive, considered an advantage in warfare in this era. Wellington prefers to wait, moving individual batteries into action as circumstances dictate. Thus he keeps his guns uncommitted until Napoleon’s cavalry or infantry are within 1000 to 1200 meters range, using solid shot. When they are within 300-400 meters, he opens up with case shot in his guns and howitzers, sometimes double-loading the last round or two.

Estimates after the battle are that Wellington’s artillerymen accounted for 60-120 casualties per gun per hour, about 33% of the overall casualty total, far higher than the proportion of artillerymen in his army (about 10%).

Joining Battle, Waterloo, June 18, 1815

An overconfident Napoleon makes another fatal miscalculation—he decides not to attack until late morning, to give the ground a chance to dry after the heavy rain from the previous night, and give his army time to eat breakfast and clean and dry their weapons. The Prussians now have enough time to march from Wavre to Mont St. Jean.

Napoleon masses several of his batteries by the farmhouse at La Belle Alliance to attack the center of the allied positions, about 1000 meters away. The British observe this line of deploying gun batteries with growing unease. French artillery officers scan the British lines looking for heavy troop concentrations and other targets such as gun batteries.

The First Thrust—Napoleon Attacks Hougoumont Farm

Fierce fighting gets underway on Wellington’s right flank at a farmhouse called Hougoumont at 11:30 a.m. Napoleon wants to reduce this farmhouse, occupied by 2,000 British Guards, so he can break Wellington’s right flank and roll up his lines. Wellington orders counter battery fire from Captain Mercer’s battery of the Royal Horse against French guns that are supporting Price Jerome’s attack against the Hougoumont farmhouse.

The Battle Royale Commences

Napoleon’s orders to his gunnery chief Desales, are “to astonish the enemy and shake his morale”. The French are positioned on a downward slope that eventually reverses to become an uphill rise on Mont St. Jean. Most of Wellington’s men hide on the reverse side of this gentle slope, out of sight of the French.

The battle erupts in full force when the Napoleon’s Grand Batterie opens fire between noon and one o’clock. Witnesses describe the roar of the batteries opening up as drowning out all other sounds, the ground shuddering with each cannonade. The thunder of the cannon could be heard in Brussels.

*Suggested subhead Effects of the French Cannonade The massed guns compensate for the distance. Effects of these salvos live up to the French artillerymen’s nickname for their guns (“le brutal”). However, most of the barrage passes over the front line and descends amidst the second line of troops waiting on the reverse side of the ridge, causing some losses and “carrying a head off here and there”.

The bombardment from 72 French guns averages 120 shots per minute, dispersed along a front a thousand yards long. Fortunately, the rain-softened ground absorbs the force of the cannonballs so they don’t bounce very far. Thus Wellington’s losses are acceptable despite some nasty direct hits on troops and gun batteries. Some British artillery caissons are hit by French fire, disappearing in huge explosions. A few British batteries, running out of ammunition, harness their guns to the horses and retreat from the inferno. Other British artillerymen mount counter battery fire with some success.

The Battle Rages on—Prussians appear on the Battlefield

Napoleon’s cavalry and infantry thrusts are met solidly by the allied forces’ steadfast defense, and occasional cavalry counterthrust. By late afternoon around 4 p.m., the first of 52,000 Prussians started battering against Napoleon’s right flank in the small villages of Plancenoit and Papelotte.

The French Cavalry Charges and British Form Square

Napoleon now tries to force a quick end to the savage battle before more Prussians arrive. His artillery ceases firing and a large mass of French cuirassier (cavalry) advance, shouting “vive l’Empereur”. The earth beneath them thunders and vibrates from the masses of horse’s hooves striking the ground.

The Allied forces form Defensive Square in an enormous checkerboard pattern. It’s a fantastic spectacle: dozens of squares with sixty feet long sides, each packed with 500 men wearing red, green and orange jackets. Long rifles with bayonets stick out at an angle to create a hedge of bayonets, scaring away the horses.

Frustrated French cavalrymen dash between the squares looking for a way in to wreak their havoc, cursing at the British, who jeer back. Officers in the middle quickly dispatch a few cavalrymen who manage to force their way into squares. Maimed horses and their dead riders lie askew, covered in blood, dirt, and black soot from the guns, brought down by rifle fire from within the squares.

The exhausted French fail to break the allied lines and squares. Even Napoleon’s artillery that has moved up the hill and is now firing on the squares from a few hundred meters is frustrated—the British lie down and escape the worst of the shot. And here is where Napoleon makes his fatal mistake. Cooperation between Napoleon’s cavalry and artillery is ineffective, and the artillery is not able to decimate the squares with shot, so the cavalry cannot get amongst the infantrymen to slaughter them with their long heavy sabers.

Meanwhile Captain Mercer of the Royal Horse Artillery refuses to shelter in the squares (surely meriting a Victoria Cross), and his battery of 6-pounders continuing to pound the French cavalry to terrible effect, as they withdraw after each charge to regroup. The French cavalry is spent, and Blucher’s Prussians appear on Wellington’s left flank, bringing with them 64 guns. They arrive just as the tide is turning against Wellington’s exhausted forces.

The Old Guard is decimated in their final charge

La Haye Sainte, the farmhouse in the center of the battlefield is finally taken by the French. It’s been the thorn in their side all day, as they attack Wellington’s center. Then in a last ditch effort to force the issue he orders his Old Guard into a final charge at 7:30 p.m. These elite soldiers march up the middle of the battlefield, now strewn with tens of thousands of torn bodies. Initially the Garde Imperiale meet some success by breaking the weakening British line in the center, but are surprised by British troops lying in wait on their flank in high corn.

Wellington, still retaining his composure despite the exhausting day, moves three horse batteries to enfilade the flanks of the Old Guard column, taking a terrible toll on the Garde Imperiale. Their charge fails. It turns into a rout—the French falling back in disarray with Blucher’s Prussians pouring out of the left flank, hot on their heels. Wellington stands on the stirrups of his horse waving his hat in the air to sound the general charge.

What became of Napoleon’s artillery after the battle? Large masses of artillery, equipment and ammunition wagons were left on the battlefield in the wake of the French retreat. One account tells of 78 guns being captured during the retreat.

Remnants of the Waterloo Battlefield Today

A surprisingly large number of museums, buildings, and monuments stand near the Battlefield today—enough to take up two full days of sightseeing for the aficionado.

At Ligny many farmhouses still stand where Blucher’s Prussian infantry held against the French attack for several hours. An enormous French gun stands on display at a busy crossroad in Ligny with a memorial plaque mounted on the wall next to it. There’s a small Napoleon museum in Ligny worth visiting.

Quatre Bras is now a major intersection, with memorials and plaques littered all along the east-west axis road.

The farmhouse where Napoleon stayed the night before the Battle, Le Caillou, is a museum now. It contains a number of historic artifacts belonging to Napoleon, and other objects recovered from the battlefield.

Visit the Waterloo church across the road from Wellington’s museum in downtown Waterloo to see dozens of moving epitaphs for British soldiers killed in the battle.

A Wounded Eagle memorial to Napoleon’s troops stands near La Belle Alliance where Napoleon spent most of the day during the battle, and later where Blucher and Wellington met. Here they agreed on Blucher continuing the chase.

La Haye Sainte still stands, also a working farmhouse; but its gates are generally closed to visitors. Nevertheless you can still walk down the busy road next to it and view it from the outside.

An enormous man-made hill in the epicentre of the battlefield, named the Butte du Lion enables the visitor to get an eagle-eye view of the battlefield, after ascending a long row of steps. At the base of the Butte is a cluster of tourist attractions depicting the battle, including a Waxwork Museum with models of the major players in the battle set against reconstructed backgrounds. A circular building portrays a 360-degree panoramic mural of the battle, including piped in smoke and sounds of gunfire.

The Visitor’s Center has an audiovisual show on the sequence of events in the battle, and an entertaining 20-minute film about a group of Belgian kids who find themselves caught in a time warp where they are transported back to the battle. Some of the scenes in the film are cut from the film “Waterloo” made in 1971, still regarded as a classic.

Wavre still has a number of historic sites where Blucher’s Prussians fought the chasing French, including a church with a cannonball still embedded in one of its pillars.

Thus there is plenty to see around the battlefield. Plan on spending another day or two sightseeing in Brussels with the amazing medieval cobblestone square, The Grande Place, in the center of Brussels. The Royal Museum of Military History at Parc du Cinquantennaire and the beautiful cathedrals sprinkled around the city are worth visiting. Of course no trip to Belgium is complete without sampling its culinary delights; mussels, waffles, chocolate and strong beers for which it is renown.

References

The Waterloo Campaign, June 1815, Albert Nofi, Combined Publishing, Pennsylvania. 1993.

The Battle: A History of the Battle of Waterloo, Alessandro Barbero, Atlantic Books, London, 2003.

Waterloo: In the Footsteps of the Commanders, Jonathan Gillespie-Payne, Pen & Sword Military, 2004.

Waterloo: A Guide to the Battlefield, David Howarth, Pitkin Guides, Hampshire, 2005.

Hougoumont, Julian Paget and Derek Saunders, Pen & Sword Books, 2001.

Return from Battle of Waterloo to Military History

Return from Battle of Waterloo to Home Page