Running Training:

4 Techniques

to Race Faster on Less Mileage

By Roy Stevenson

As we age and our time becomes consumed with work, family, and other interests, we find ourselves feeling the pinch when it comes to running training. Often it's the first thing to be sacrificed or be cut back.

This need not be--you can still improve your race times in distances up to the half-marathon by running less mileage if you have a reasonable conditioning background, or have been running for several years.

Dr. David Costill, one of the foremost exercise physiologists in the world, found that runners continue to improve their oxygen processing capacity (known as VO2 max) linearly in tandem with running up to 80 kilometres (or about 50 miles) per week. Past that, it appears your oxygen consumption approaches your genetic potential. Thus running more than this may not be time well spent if you have limited time for running training.

Furthermore, many studies have shown that running as little as three days per week results in marked improvements (4.8%) in VO2 max. Another interesting trial revealed that even for longer distances such as the marathon, running as little as three days per week results in excellent marathon performances. The astonishing results of this experiment confounded proponents of the 100 miles per week camp.

Here's what happened in this experiment. Twenty-five runners were put on a three-days-per-week marathon running training schedule using the FIRST training program at Furman University. They performed one tempo session, one speed session and one long endurance session each week plus additional cross training such as cycling or strength training.

After 16 weeks, 21 of them started a marathon, with all finishing. Amazingly, 15 ran personal bests, and 4 of the remaining 6 ran faster than their previous marathon. Clearly, running low mileage did not prevent them from running a full marathon, and in the majority of cases resulted in personal records.

Another study found runners who cut back their running time by 32% and substituted this running time with weight training sessions, improved their 5K times significantly.

In fact, you'll be surprised at how much you can improve by simply cutting back on your running training for several months.

It's widely acknowledged by coaches and exercise scientists specialising in running that 65% of runners at all levels have been over trained at some point of their running career, so there's a good chance you are one of them.

Many runners find this out by accident-they get injured, are forced to rest up for a week or so, then come out and race their best ever, much to their complete surprise.

We are compulsively driven to train as much as we can in the mistaken belief that more is better. Some times, such as during your off-season conditioning phase, this may be the case. But most of the time you'll be amazed at what you can do on less running.

How, then, can we change our running training schedules to squeeze more out of ourselves? It's all about increasing intensity. Here are the three factors coaches take into account when designing your running training programs:

* Frequency - The number of training runs we do each week

* Intensity - The pace or speed we do the running sessions. i.e. quality.

* Duration - The length or time of our running sessions.

It makes sense that if we must cut back frequency and/or duration, we'll need to increase intensity to compensate. So, most of this advice revolves around pushing your pace one way or another. The theory is simple: if you want to run a sub 40-minute 10K (about 6:27 per mile), for example, you've got to become efficient at running at that pace by improving your speed endurance.

Four techniques you can use to improve the quality of your running follow--but first a few ground rules before you dash off and run yourself into the ground.

Running Training: Ground Rules

* Warm up properly before doing any of the following techniques. A 10-15 minute jog and a few stretches will suffice.

* Plan several more recovery days of jogging into your schedules between the high intensity workouts. You'll be running at a higher intensity, so you'll need shorter recovery jogs between interval, hill or time trial days

* When are you ready for your next high intensity workout? Your legs will no longer feel tight or sore. In healthy runners this should take about 48-72 hours.

* Show flexibility with your new approach. It takes your legs different periods of time to recover, depending on your diet, and myriad other factors. You will get into trouble if you insist on setting a hard and fast day-by-day training schedule.

* Important Recovery Tip: Do as much of your running on grass and dirt trails as you can manage. The absorbency of these surfaces is much greater than the road, and your legs will love you for it.

As you can see from the list above, recovery is the secondary key to improving your times on less running than intensity. You must allow your muscles, tendons, ligaments and connective tissue to get stronger and more tensile. This is called the anabolic rebuilding process, where proteins and collagens enter the muscle cells and repair microscopic tears in your muscle fibres.

Lactic acid, metabolites and other waste products must also be given time to flush out of the muscle, and this must all happen before you proceed with your next high intensity running training session.

Four Techniques to Improve Race Times on Less Running

Here are four techniques to improve your race times on less running time per week, and even less days of running. I believe you can cut back your total running training mileage by up to 33% without negatively affecting your racing times.

Running Training Technique #1: Run Your Hills Faster

Okay, I never said it would be easy. When you come to hills on your training routes, accelerate up them gradually, maintaining a sub maximal pace that's just below your maximal threshold. I.e. you're running just below the point where, if you speed up any more, you'll end up walking or slowing down a lot.

Concentrate on your arms driving harder and lifting your knees a little higher, but still striving for holding your form well. Your aim is to become smoother while running faster on the upgrade.

This is tough and it will take two to three weeks for you to adapt because uphill running is physically and mentally daunting. You're trying to condition yourself to automatically speed up when you hit hills, so it becomes almost an instinctive reflex.

You'll find in your early uphill efforts you'll have to slow down. If you persist with this, going a little further on each outing at your faster pace, your breathing will get easier and your legs will not feel so fatigued and heavy.

Eventually you'll be able to crest the hill at the same pace you started at. Also, when starting out, you won't be able to do this on every hill, so hit every second hill in this manner. As you adjust, bring in the rest of the hills.

Another variation is to select one steady uphill slope and do a number of repeats up it. Start with 4 uphill fast running bursts over a distance of 100 to 200 metres, and walk or jog slowly back down to the start. Increase your repetitions to 6, then 8 then finally 10 each subsequent session.

The big payoff for hill training is when you come to a hill in a race, you'll be hammering up it and wondering why everyone around you is falling by the wayside.

Running Training Technique #2: Do A Time Trial Every Two or Three Weeks

These high intensity efforts are physically and mentally grueling and thus should only be done once every two or three weeks. Also known as tempo runs, time trials are an easy concept.

They originated with legendary New Zealand coach Arthur Lydiard. In his book Running The Lydiard Way he says, "The idea is to run trials under or near the distance you are training for. For 10,000 metres use mostly 5,000 meters with an occasional 10,000". He continues, "Time trials are most important in bringing about coordination of speed and stamina".

Choose a flat measured distance on a road or track and warm-up for 10-15 minutes jogging followed by a few stride-outs over 50 metres. Then chose a measured distance on a road or track and push yourself over this distance at a sub maximal threshold pace.

Your goal here is to maintain a strong steady pace all the way, hence the importance of checking your pace every mile. You're aiming to finish at the same pace you started at. You should be left with some reserves when you finish a time trial, not be exhausted.

Note your finishing time, and try to better it slightly on every subsequent time trial. Ideal distances for time trials are 5K, 8K or 10K. You can rotate these each time you do a time trial.

This type of workout has several benefits. First, you become used to pushing yourself over the entire race distance, so that when you toe the start line, your body (and just as importantly your mind), are prepared for and used to thrashing yourself over that distance.

You'll find that towards the end of the race, when people are flagging and starting to slow down, you're either maintaining or speeding up. Either way, you're pulling ahead, and your time will reflect this.

Second, you learn perfect pace judgment with time trials. Ideally you should be running even paced races, so that your second half is the same or hopefully faster than, your first half. This is a very valuable skill to acquire, and gives you a tremendous advantage over the rest of the runners.

Running Training Technique #3: Do Interval Training on the Track

Track interval workouts are well defined. You run a certain number of repetitions at a predetermined speed, with a set distance of walking or recovery jogging between the fast bursts.

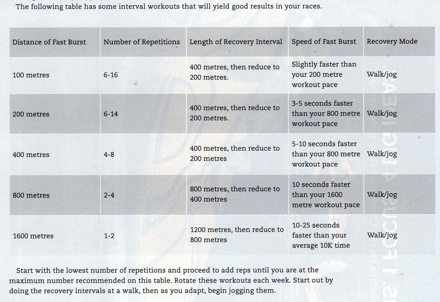

The following table has some interval workouts that will yield good results in your races:

Start with the lowest number of repetitions and proceed to add 1-2 reps/week until you are at the maximum number recommended on this table. Rotate these workouts each week. For example, on Week 1, do 6 x 100 metres, then Week 2, do 6 x 200 metres, Week 3 do 4 x 400 metres, etc., until you have come full circle.

Start out by doing the recovery intervals at a walk, then as you adapt, begin jogging them. The fast bursts should be done as recommended in the Speed of Fast Burst column.

Running Training Technique #4: Do Intervals on Cross-country--Fartlek Training

Another less restricted version of interval training is called fartlek, a Swedish word that translates into speed play. Here, you run at various speeds over forest trails, parks, and the bonny glens and moors of Scotland at will.

One of my favorite workouts is 15 minutes jog (warm-up), a hard 5-minute burst, a recovery jog of 3-4 minutes, another hard 5-minute burst, a recovery jog of 3-4 minutes, then five or six fast pace stride outs, followed by a cool-down jog.

How does this faster running training improve our performance? This list shows what happens in physiological terms when we increase the quality of our running.

* Physiological Benefits of Improving the Quality of Your Training Neuromuscular Benefits: Your leg muscles recruit more fast twitch muscle fibres when you run-these muscles fibres are the ones you call on when you pick up your pace, or when your slow twitch fibres are fatiguing.

* Running Economy/VO2 Max - Decreased oxygen extraction at sub maximal pace and increased maximal oxygen consumption at maximal pace

* Improved Lactate Tolerance - By simulating fast running in your training workouts, your body adapts by reducing lactic acid levels at any given sub-maximal workload. We call this improved lactate tolerance.

* Higher Knee Lift from Hill Running - Knee lift becomes higher when you run on the flat and uphill. This means a longer stride with the same effort on the flat, and increased running efficiency up hills.

* Tougher mental preparation for races - You become accustomed to pushing yourself when the going gets tough in races.

Putting It All Together: Designing Your New Running Training Program

Your new running training program now revolves around a series of high quality sessions with recovery jogging between.

You'll need to be flexible with the recovery jogs. Here's what I mean: the day after each high intensity workout, go out and run slowly and easily, or take a day off. Likewise the next day. Then, the following day if your legs and breathing are fine, it's time for your next high intensity workout. If not, jog again that day and see how you feel the next day.

Finally, you'll need to maintain at least one long run each week to maintain your aerobic base. Your body cannot handle high intensity sessions every day. This invites illness or injury. The length of these long, slow endurance efforts should be somewhere between one and two hours, always done at a slow jog, so your legs will not be sore the next day.

If you're strapped for time and have a reasonable base of running over the past few years, or are coming off a long conditioning base, these four techniques will work well for you. You'll be surprised at how much your times will come down.

You can find more running information at my running website: www.running-training-tips.com.

Return from Running Training Techniques to Triathlons & Multisport Return from Running Training Techniques to Home Page